Panama Canal Transit

Thursday, January 16, 2020 at 06:30PM

Thursday, January 16, 2020 at 06:30PM

December, 2019

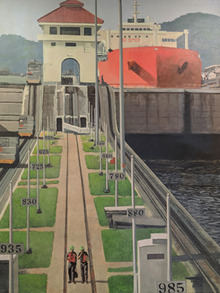

From the observation lounge of the 1920's oil painting Miraflores Locks Star Pride, we marvel at a string-of-pearls of lights against the dark sea horizon twinkles from a dozen and a half ships in the near distance, lined up to wait their turn the next day to enter and transit the Panama Canal. On a previous jaunt to Panama City, we had seen the Miraflores locks, sited at the western end of the canal, from afar on the public viewing platform. Now we will have a chance to experience the entire length of the canal as the Windstar ship approaches the lowest lock from Balboa Harbor and prepares to enter.

1920's oil painting Miraflores Locks Star Pride, we marvel at a string-of-pearls of lights against the dark sea horizon twinkles from a dozen and a half ships in the near distance, lined up to wait their turn the next day to enter and transit the Panama Canal. On a previous jaunt to Panama City, we had seen the Miraflores locks, sited at the western end of the canal, from afar on the public viewing platform. Now we will have a chance to experience the entire length of the canal as the Windstar ship approaches the lowest lock from Balboa Harbor and prepares to enter.

The first canal across the Isthmus of Panama was attempted by the French in 1881. They misguidedly believed that they could dig through at sea level, and abandoned the project due to engineering difficulties, and with a high rate of worker death—over 20,000 died during the French attempt, mostly from yellow fever and Malaria. The US took the project over in 1904, and the canal and locks were completed in just 10 years. The Chagres River was dammed to create Gatun Lake, through which the main portion of the transit occurs. Filled by plentiful rainfall, the lake is also the source of the millions of gallons of water that run through both the Atlantic and Pacific lock systems and into the respective oceans.

Each lock in Miraflores is 1,050 feet long, and 110 feet wide, with a depth of almost 40 feet. The locks are in side-by-side pairs, allowing ships to traverse in both directions at the same time. A ship that fills the lock almost entirely is known as a Panamax vessel, and has barely a foot of clearance on either side, and just a few front and back. Such a ship, stacked dozens high with containers, is in the second lock just ahead of us.

An hour earlier, the first of a series of canal pilots boarded the ship to guide it through the first two sets of locks. There will be other pilots for other sections of the canal. As the ship slowly approaches the open lock doors, two men descend a ladder at lock-end, step into a small rowboat, and row out to take a rope thrown from the ship. They row that back to the lock, where it is attached to stout steel cables that are pulled back to the ship at each corner, and attached. These cables run to the “mules” the 55-ton, 580 HP Mitsubishi electric rail engines, which will keep the ship centered in the lock, and slowly pull it into place behind two

locks. There will be other pilots for other sections of the canal. As the ship slowly approaches the open lock doors, two men descend a ladder at lock-end, step into a small rowboat, and row out to take a rope thrown from the ship. They row that back to the lock, where it is attached to stout steel cables that are pulled back to the ship at each corner, and attached. These cables run to the “mules” the 55-ton, 580 HP Mitsubishi electric rail engines, which will keep the ship centered in the lock, and slowly pull it into place behind two  pleasure craft at the lock’s head. The original mules were made in the US by GE, and cost $20,000 each. The current Japanese models run $2.5 million each.

pleasure craft at the lock’s head. The original mules were made in the US by GE, and cost $20,000 each. The current Japanese models run $2.5 million each.

The rear lock gates—over seven feet thick to contain the enormous weight of water—slowly close, and over the course of about 15 minutes, the lock fills with over eight million gallons. The front gates open very deliberately, and our two pleasure escorts and the Star Pride move sedately into the second chamber, guided by the mules, which running on a cogged rail, have to climb a short, steep incline to ascend to the next lock level. The gates through which we just passed close, water enters, ships rise, front gates open, and we move out into Miraflores Lake. A short while later we go through the same process at Pedro Miguel locks, and we are now about 85 feet above sea level. From here, the  Gaillard or Culebra Cut—which was dug through the continental divide to complete the canal—runs about 8 miles where it widens into Miraflores lake. The slow cruise through the Cut and Lake takes about four hours—a normal complete canal transit takes 8-10 hours, depending on the vessel. We pass huge container ships, dry bulk carriers, oil tankers and smaller craft going the other way, but no other cruise ships at which to wave from the railing.

Gaillard or Culebra Cut—which was dug through the continental divide to complete the canal—runs about 8 miles where it widens into Miraflores lake. The slow cruise through the Cut and Lake takes about four hours—a normal complete canal transit takes 8-10 hours, depending on the vessel. We pass huge container ships, dry bulk carriers, oil tankers and smaller craft going the other way, but no other cruise ships at which to wave from the railing.

The day before we had driven past the Gaillard Cut to the small port and resort of Gamboa to embark on a boat cruise of animal viewing—an aquatic game drive—and we now curve past the small islands on which we saw toucan, macaws, and the approachable tamarind monkeys, as well as sour-faced, nasty capuchins and hooting howler monkeys cavorting in the trees.

The day before we had driven past the Gaillard Cut to the small port and resort of Gamboa to embark on a boat cruise of animal viewing—an aquatic game drive—and we now curve past the small islands on which we saw toucan, macaws, and the approachable tamarind monkeys, as well as sour-faced, nasty capuchins and hooting howler monkeys cavorting in the trees.

Gatun Locks, gateway to the Atlantic—is composed of three lock chambers in a row, dropping the entire 85 feet to the Caribbean Sea in one stepped series. In the distance we see the enormous golden five-sphere liquid natural gas carrier, which we have followed on and off through the canal, entering the newer and larger Aqua Clara Locks. These, along with the new and larger Cocoli Locks on the Pacific side were completed in 2016, in order to allow ships larger than Panamax to transit the canal.

We wait some while for the locks to cycle, and reverse the process we had gone through that morning in order to drop back to sea level. The electric mules descending their steep lock-separating hills is even more precarious-looking than when they were going up. We exit the locks to complete the transit and  cruise into Limon Bay and finally wind through the Port of Colon to the quay, where gigantic roll-on-roll off automated cranes are unloading a monstrous container ship on our left.

cruise into Limon Bay and finally wind through the Port of Colon to the quay, where gigantic roll-on-roll off automated cranes are unloading a monstrous container ship on our left.

Never a bucket-list item for us, the transit of the Panama Canal was nonetheless quite interesting, and the engineering marvel, completed well over one-hundred years ago, is quite amazing to witness.

Hightower | Comments Off |

Hightower | Comments Off |